Theoretical and practical treatise on the art of making and applying varnishes, Pierre-François Tingry, 1803, 195-202. Translation by Google Translate. (Or, see this English translation, from about page 165 on.)

Those who have seen in detail the laboratories devoted to chemistry courses, will form a fairly clear idea of the construction of this furnace, remembering that which serves for the separation of the antimony sulphide from its gangue. But in order to make it serve the object of which we are speaking, we need some correctives, by means of which the liquefaction of the solid resins, and even their mixture with the drying oils, is followed without difficulty.

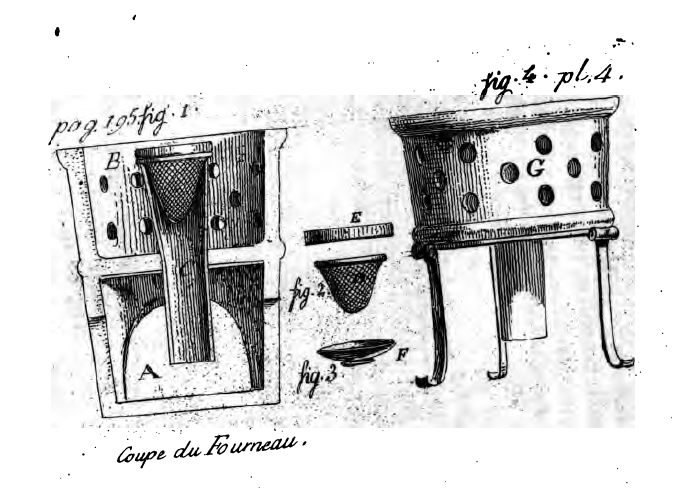

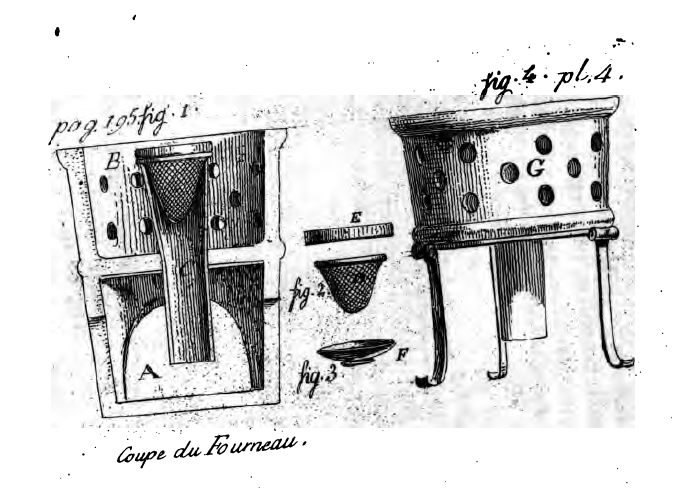

This furnace is shown in fig. 1e. Board 4th. Can be built entirely of terracotta by practicing three large openings in the lower chamber A which replaces the ashtray in the ordinary furnaces. These openings end in a hanger at the base of the upper chamber B or hearth. The arrangement of this base must be such that, in proportion to the curved openings, the pillars which start from the bottom and end in arcades are as small as possible, in order to leave to the Artist all the facilities suitable for the extraction of The liquefied matter, or even for its mixture with the siccative oil, if one always takes this kind of varnish.

The upper chamber B or the hearth of the furnace is separated from the lower part A by a floor or floor which replaces the grating of the ordinary furnaces. This floor has in its middle a circular opening, the diameter of which corresponds to that of a crucible C which it is to receive, and which extends very far into the lower part. This floor can be part of the furnace, or it is removable. In the latter case, it is supported by means of 3 spurs, or by a circular thread projecting into the interior at the level of the hangers. In my furnace this separation is composed of a sheet of sheet covered with a coating of earth with pottery, one inch thick. This last precaution is indispensable in order to remove the heat from the lower part A.

The side walls of this fireplace B are pierced with holes one inch in diameter (2.7 centimeters) and separated from one another by intervals of about 3 inches (8.1 centimeters). These openings are sufficient to fix the development of caloric (heat) to the point suitable for this kind of operation. I write here the proportions of the three parts of this furnace which served in my experiments, and in which I liquefied six ounces of copal in the space of ten minutes, without altering its cost too much. (M)

(M) Overall stove height - - - - - 17 1/4 inches (4,7,3 decim.)

Height of the lower chamber A including the base that is 1 inch thick - - - - - 11 inches (2.9 decim.)

Height of the upper chamber B of the laboratory - - - - - 5 1/2 inches (1.4,3 decim.)

Diameter taken from upper edge and inside of hearth B - - - - - 9 1/2 inches. (2.5.8 decim.)

Diameter of the same piece taken from the floor - - - - - 7 inches. (1.8 decim)

This part has two and a half inches of retreat and it expresses the diameter of the whole lower part of the furnace A.

The shape of the crucible C is very well represented by that of a horn to be played with the dice, the bottom of which would have been suppressed. This crucible has to extend 9 1/2 inches. (2.5.8 decim.)

Its diameter

Superior 4 1/2 inches. (1,2,1,5 decim.)

Lower 2 1/2 inches. (6.3.5 centim.)

The screen D of conical figure has the same diameter as the upper part of the crucible and extends until the birth of the separation floor.

The crucible C is placed in the opening in the middle of the separation floor, so that it rises 3 to 4 inches in the hearth. A point of union with the floor is provided for the fall of ashes or small coals.

Once this arrangement is complete, a kind of screen D (see Figure 2) is placed in the crucible, made of a brass lattice, of a rare (fine?) fabric. This lattice is given the shape of a funnel whose edge is secured around a circle of iron wire or leon bearing the same diameter as the upper part of the crucible C. The retreat experienced by the crucible C in Its form contributes to the stability of this kind of sieve, just as the well-pronounced conical shape of this latter part shelters it from contact with the lateral part of the crucible, an important object for preserving the copal from too great a alteration.

The copal is then placed on this metallic filter in pieces of the size of a small hazelnut, and in various fragments below this size, and the whole is covered with an iron cover E of an inch in thickness, having Care to fill the joint with a soggy earth-leaf to remove any communication with the outside air.

On the other hand, the lower part of the crucible C is filled in water in a shallow saucer F (see FIG. 3) so that it plunges into water from two to three lines ( 6.7 millimeters).

The firebox B is filled with lighted coals up over the iron lid. The first impression of caloric (heat) on the copal is announced by a kind of sparkle resulting from the dilation which reduces it in small splinters. This noise is a precursor very near to liquefaction; it takes place soon after. Then a small palette of iron terminated by a bent tail is insinuated under the cylinder, and it is given the proper motion to precipitate the liquefied portion of the copal under water, and to bring it back into the solid state towards the edges of the saucer . When the operation is finished, the copal is exposed on dry cloths, or on papers with a glue, in order to sprinkle it; It is then piled up and exposed to a gentle heat, to make it lose all its moisture.

During the pouring of the copal, a very delicate portion of oil is separated which remains fluid after the operation. She swims on the water as well as the copal, and gives the latter a bold look. But when the cylinder is sufficiently prolonged, it may be dispensed with making it dive under water, and even to receive matter in water; But a smoke escapes, which may displease the artist. The essential point is to spare the fire so as not to alter the color of the copal. It is recognized that the fire is too lively, when a very thick smoke emits from the lower opening of the crucible; That it is very red, and that the drops falling into the water rise in bladders and make small explosions.

I succeeded in composing the Varnish with oily oil in the same operation, by replacing the water with boiling drying oil, and by maintaining it in this state by means of a mass of hot iron Which served as its support. Mixing of the liquefied material is facilitated by means of a bent spatula; And afterwards the boiling essence is added. One feels the inconvenience of placing under the apparatus itself a volatile and highly inflammable oil.

I will insist more and more sure on the isolated liquefaction of the copal than on the possibility of supplementing its mixture with a drying oil, to make it into a Varnish of the 5th. kind. This new method enables the artist to compose a tréssolide varnish, very little colored, and to dispense with that of copal to drying oil whose composition requires processes which alter the essential qualities of the substance which makes it the base. I can see the time when the artist, freed from all routine prejudices, will confine himself to the use of varnish, of which I here give the formula as cleaner than that of the fifth. To respond to the celerity of the work of printing, and to the views which are proposed, as to the sharpness and solidity of the varnish.

For larger work, the dimensions of this stove may change; But it would be proper to establish the focus properly so called, on a kind of tripod of iron, as shown in Fig. In order to leave the manipulator more comfortable; But I will always insist on the advantage of working only on doses of 4 and 6 ounces (about 183.43 grams) the ease of putting back the material, when the lid joins very well, pronounces on the preference that Small doses should be given over large ones; The copal is less altered. In this case, it is possible to use a metallic cylinder which is joined to cover with the cover. Then the same fire might serve two or three streams.

The precious advantages which are attached to this new method will be felt when the resulting varnishes with gasoline have been tested. The copal thus prepared has different and more extensive properties than those which are given to it by the ordinary method; And it does not have the dark and brown color which it takes at a temperature too high and too prolonged. Plunged here in an atmosphere of caloric (heat), it receives the impression only on the surface which, soon yielding to the power of this agent, escapes, under the liquid state, to the continuation of its action ; New surfaces successively undergo the same effect, and the final result is a copal which is the least altered, and which can not have undergone but a slight modification in the principles of its composition; Between its parts, and which placed so great an obstacle to the solutions sought to be made. Finally, it is possible to compose fatty varnishes with copal, almost without color, using a little colored oil, such as that of carnations, prepared in lead vases, according to the method of Watin.

Similarly, this copal, simply modified, may increase the solidity of the varnishes in alcohol in a more direct manner than when employed in the preliminary preparation. A second liquefaction would give it the property of being more soluble in alcohol; But it would be to be feared that the alteration in its principles, pushed farther, would give it no superiority over the resins most soluble in this liquid. I will finish all that relates to this 4th. Kind of varnish by the exposition of the experiments which I have made by applying our copal, thus prepared, to the most popular vehicles.

Many thanks to Stephen A. Shepherd's Shellac, Linseed Oil, & Paint - Traditional 19th Century Woodwork Finishes for pointing me to this. Here's a picture of one he had made. He even had them for sale at one point, though they don't appear to be there now. I haven't tried one yet, but soon...